During The ‘Super Wolf Blood Moon’ Eclipse, A Meteorite Struck The Moon

Viswamitra Jayavant - Feb 01, 2019

A meteorite strike has been recorded on tape and in picture during the Super Blood Wolf Moon on January 21st, making it the first impact event ever to be recorded during a lunar eclipse.

- Fireball Crashed Near A Railway Station In Ghaziabad, Locals Panicked

- Scientists Discover That Earth's Atmosphere Stretches Beyond The Moon

- Galaxies Without Dark Matter Are Real, Two New Studies Confirm

A relentless, 10 years long search ended for an astronomer at the University of Huelva in Spain just a few days ago when, for the first time, he captured the brief flash of a meteorite impact on the surface of the Moon in the reddish light of the lunar eclipse. The luckiest scientist of the day is Jose Maria Madiedo. And his life’s turning point happened at 5:41 A.M. Spanish Peninsular Time during the lunar eclipse with the worst sounding name ever: “Super Blood Wolf Moon”.

Astronomy 101: Meteorite Strike

Meteorite strikes are one of the most violent occurrences in the Universe.

Depending on the size of the meteorite itself, the energy released during an impact event can range from that of a small bomb. To extinction-level events that can cause the kind of catastrophe that could wipe out all life on the planet. As horrific as that sounded, it is not something our planet had never seen before.

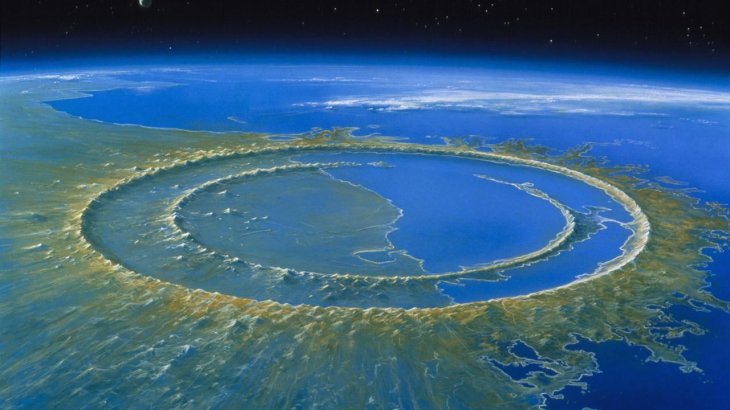

The Cretaceous-Tertiary extinction event approximately 66 million years ago which wiped out some 75% of all life on Earth was believed to have been caused by an asteroid some 10 kilometers in diameter. The event released roughly 21 to 921 billion times the energy of Little Boy - the American atomic bomb that pulverized Hiroshima at the end of the Second World War. The remainder of this event can still be found on the map today in the form of the massive, 150-kilometer across impact crater named ‘Chicxulub’ in Mexico, by the Yucatán Peninsula.

In fact, impact events are extremely common in the Universe. In spite of the size that’s almost incomprehensible for us, celestial bodies tend to always find each other. That is the reason why the Moon’s surface and a vast multitude of other bodies’ surfaces are scarred with craters and marks of violent events in the past.

Earth is considerably more fortunate as it is protected by the thick, local atmosphere which acts as a natural aerobrake to slow down meteorites. Bleeding out their vast energy in the form of light and heat, causing a streak of light that can be visible on the night sky that is colloquially called: ‘Shooting star’. Shooting stars often broke apart and disintegrated as they’re often small-sized meteorites less than a meter across. However, the lights from larger bodies several meters across can be seen, and even be blinding during the day like the Chelyabinsk Event in 2013.

The Moon doesn’t have the luxury of a thick atmosphere, therefore, meteorites often fall unopposed onto the surface. Scattering impact craters and deep trenches all across the surface of the Moon. In fact, 2,800 kilograms of materials made an impact on the Moon every day. But sizeable impacts - the kind that can cause a flash of light - are rarer, though certainly not improbable. Scientists know that they occur often, but seldom ever caught them on tape or during such an exotic event as the lunar eclipse.

That ended now.

The Event

Millions of people looked up to the night sky on Monday to view the breathtaking “Super Blood Wolf Blood Moon” lunar eclipse. Those who can afford the location get to see the appearance of the reddish aura in person. And those who cannot view the event through live feeds. Many of the on-site viewers, unfortunately, did not know that another astronomical event considerably more interesting than just a shift in color had also happened.

Online viewers who have a better view of the Moon through cameras with high power magnification noticed a tiny, passing flash. Many believed immediately after that it was the product of a meteorite striking the Moon.

Jose Madiedo confirmed on Twitter the suspicion that, indeed, an impact event had occurred during the eclipse’s totality at 5:41 A.M. SPT. The photograph posted by Madiedo brought the flash into focus and is clearly visible at the darkened top left. The location of the impact on the dark side of the Moon contributed further to its timely discovery. Itself being a blinding contrast against the dark background of the dark side of the Moon.

It was the first time ever that a Lunar impact event was recorded during an eclipse.

MIDAS

Due to the significance of impact events and the plethora of the knowledge it can give scientists regarding the Universe, efforts to monitor Lunar impact events dated back to 1997 that eventually culminated to MIDAS: Moon Impacts Detection and Analysis System. MIDAS is a joint survey project led by the University of Huelva and the Institute of Astrophysics of Andalucia. Madiedo joined the MIDAS Project in 2008 and has been a key member of the initiative ever since.

MIDAS is composed of “small telescopes and high-sensitivity CCD [Couple-Charged Device] video cameras”, all of which are pointed at the Moon and run continuously during scheduled observations. Custom-built software is used to analyze the data collected by the devices, and they are so efficient they can detect an impact 0.001 second after it had occurred.

“We monitor the nocturnal region of the Moon to identify impact flashes. In this way, these flashes are well contrasted against the darker background,” Madiedo said during an interview.

That’s not all MIDAS can do on its own. Aside from detecting and verifying the occurrence of a Lunar impact event. It can also calculate the exact location of the impact. In 2015, the project was given a hardware upgrade and photometric filters were added onto the telescopes and cameras employed. Now, MIDAS can also analyze the temperature of the flashes to determine the energy that the event released.

Before the January 21st event, MIDAS had never recorded an impact occurring during a total lunar eclipse. Explaining the rigorous schedule of the project, Madiedo explained: “So, we usually monitor the Moon about five days after the New Moon, and around five days before the New Moon. We also monitor during lunar eclipses, since during these eclipses the lunar ground is dark.” In spite of the continuous effort put into detecting a Lunar impact event during an eclipse put forth not only by the MIDAS Project but also other teams worldwide, none has ever succeeded before MIDAS finally beat them to it.

It was fortunate that the team has decided to kick the project into overdrive in preparation for the eclipse. Usually, MIDAS only runs on four telescopes. But this time, they decided that it’d be worth the investment to double the number and arrange for simultaneous operation of eight telescopes at once.

“But I made the extra effort to prepare the new telescopes because I had the feeling that this time would be ‘the time,’ and I did not want to miss an impact flash.” Said Madiedo. It turns out to be a correct hunch that he had had, and the extra investment netted them a valuable discovery of a lifetime. “I was exhausted when the eclipse ended—but when the automatic detection software notified me of a bright flash, I jumped out of my chair. It was a very exciting moment because I knew such a thing had never been recorded before.”

The preparation and operation of the extra telescopes did not go without a hitch, though. During the observation, one of the telescopes suffered a technical problem and went down mid-way. Fortunately, the other seven performed their job perfectly.

The team estimated that the frequency of such an impact wasn’t as rare as it should be. Only around once every seven to ten days. However, I’m fairly sure that the frequency of one happened right in the middle of a lunar eclipse is dramatically lower. The flash was believed to have been caused by an asteroid about ten kilograms in weight.

The Value

By analyzing the data and aggregate it with historical data, scientists can build a data set to forecast the rate of Lunar impacts. And, due to the natural satellite’s distance to Earth, connect it back to the planet and estimate the rate at which similarly-sized asteroids cross path with Earth.

In fact, the data that scientists gathered by observing the rate of impact on the Moon had led them to believe that the probability of having an impact event on Earth has jumped in frequency 290 million years ago. The finding alone justifies as to why it is so important to maintain our eyes on our natural satellite. We and the Moon share an intimate history that, once learned, might be able to save our lives one day in the future.

Featured Stories

Features - Jan 29, 2026

Permanently Deleting Your Instagram Account: A Complete Step-by-Step Tutorial

Features - Jul 01, 2025

What Are The Fastest Passenger Vehicles Ever Created?

Features - Jun 25, 2025

Japan Hydrogen Breakthrough: Scientists Crack the Clean Energy Code with...

ICT News - Jun 25, 2025

AI Intimidation Tactics: CEOs Turn Flawed Technology Into Employee Fear Machine

Review - Jun 25, 2025

Windows 11 Problems: Is Microsoft's "Best" OS Actually Getting Worse?

Features - Jun 22, 2025

Telegram Founder Pavel Durov Plans to Split $14 Billion Fortune Among 106 Children

ICT News - Jun 22, 2025

Neuralink Telepathy Chip Enables Quadriplegic Rob Greiner to Control Games with...

Features - Jun 21, 2025

This Over $100 Bottle Has Nothing But Fresh Air Inside

Features - Jun 18, 2025

Best Mobile VPN Apps for Gaming 2025: Complete Guide

Features - Jun 18, 2025

A Math Formula Tells Us How Long Everything Will Live

Read more

ICT News- Feb 20, 2026

Tech Leaders Question AI Agents' Value: Human Labor Remains More Affordable

In a recent episode of the All-In podcast, prominent tech investors and entrepreneurs expressed skepticism about the immediate practicality of deploying AI agents in business operations.

ICT News- Feb 18, 2026

Google's Project Toscana: Elevating Pixel Face Unlock to Rival Apple's Face ID

As the smartphone landscape evolves, Google's push toward superior face unlock technology underscores its ambition to close the gap with Apple in user security and convenience.

ICT News- Feb 19, 2026

Escalating Costs for NVIDIA RTX 50 Series GPUs: RTX 5090 Tops $5,000, RTX 5060 Ti Closes in on RTX 5070 Pricing

As the RTX 50 series continues to push boundaries in gaming and AI, these price trends raise questions about accessibility for average gamers.

Comments

Sort by Newest | Popular