A New Theory On Fast Radio Bursts Might Be The Answer For The Source Of These Mysterious Cosmic Events

Aadhya Khatri - Mar 12, 2019

Brian Metzger, along with several other scientists around the world, has been working hard, trying to find an answer for fast radio bursts

- Scientists Discover That Earth's Atmosphere Stretches Beyond The Moon

- Galaxies Without Dark Matter Are Real, Two New Studies Confirm

- Nuking Asteroids Coming To Earth Is Harder Than We Thought

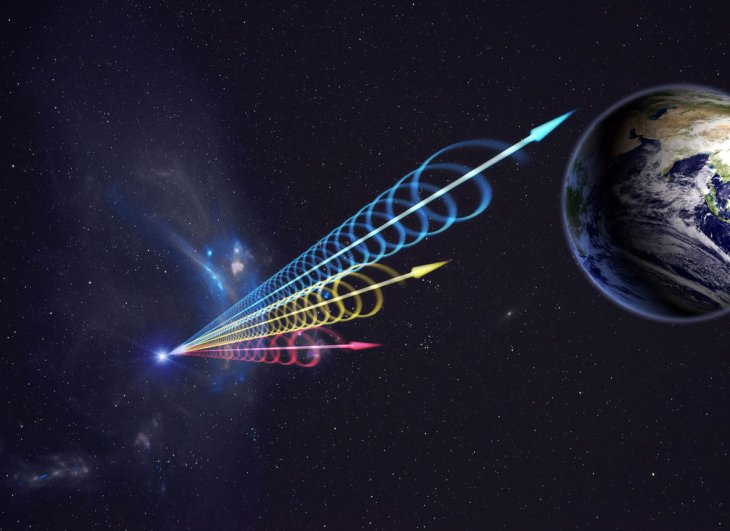

In the field of space science, Brian Metzger, along with several other scientists around the world, has been working hard, trying to find an answer for fast radio bursts. Despite lasting for a few milliseconds, these FRBs are the brightest signals in our universe, even more luminous than radio pulsars.

Ever since their existence was confirmed, scientists have come up with a lot of theories on what their causes are. As far as we know now, there are at least 48 assumptions, which even larger than the number of these FRBs.

There are at least 48 theories on the source of FRBs

Metzger and his team thought that they have finally found out the right answer and they published it on a paper on arxiv.org. The study suggests that the FRBs might be the result of explosions in areas of the universe where there are particle clouds and magnetic fields around.

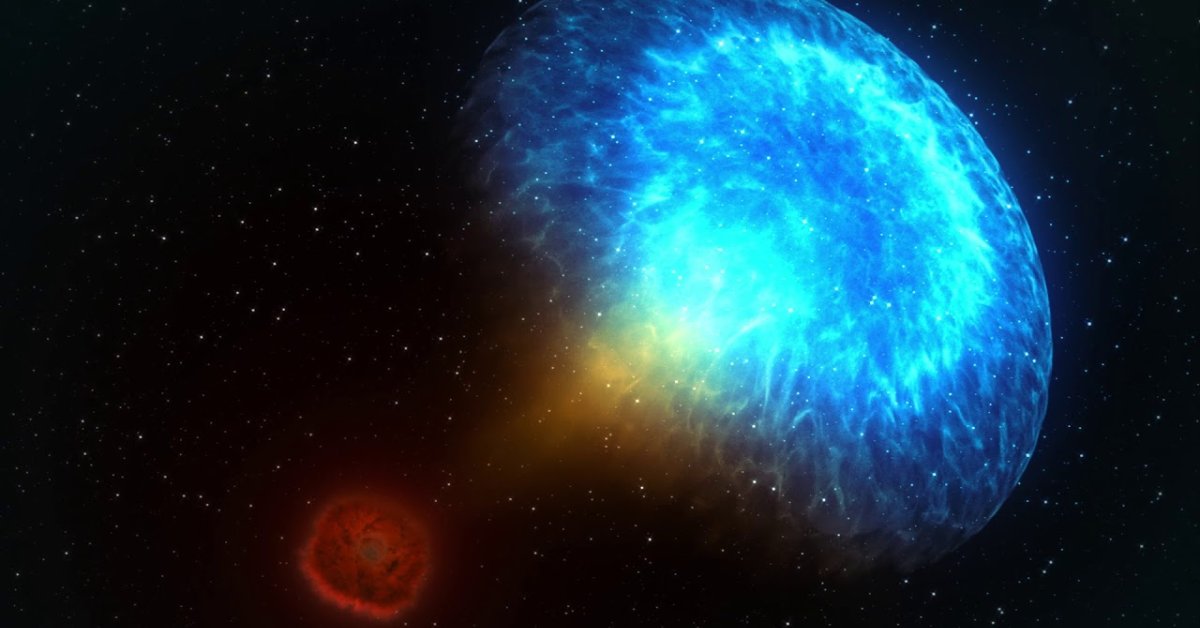

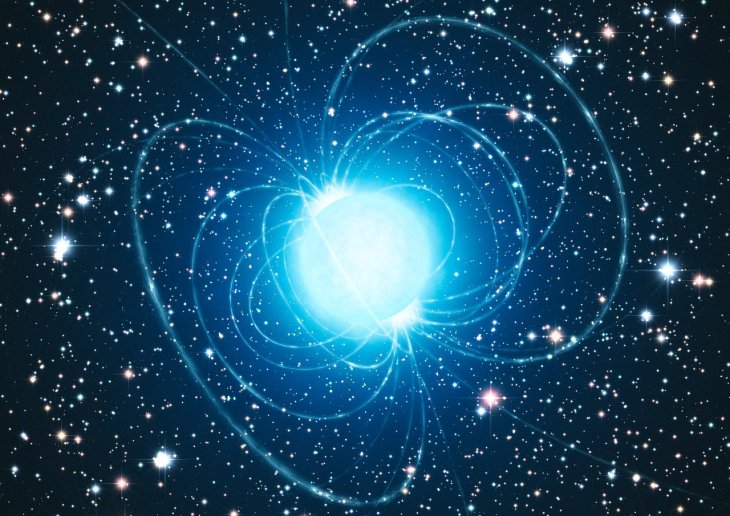

It said that a magnetar star might be the source but the explosions do not necessarily require one to happen. The magnetar is a neutron star that sometimes emits particles with the electric charge. These incidents happen at a larger scale than the usual coronal mass ejections occur on our Sun.

Whenever these particles are released, they crash into the mess around them and generate a shock wave that later turns into a burst of radio pulses to the other side of the universe.

James Cordes, a professor of astronomy at Cornell University showed his approval to this theory and said that while there were more to work on, what Metzger and his team did was prominent.

One of the advantages of this theory is that it gives astronomers a tool to predict the future FRBs, which they will also test to confirm its accuracy.

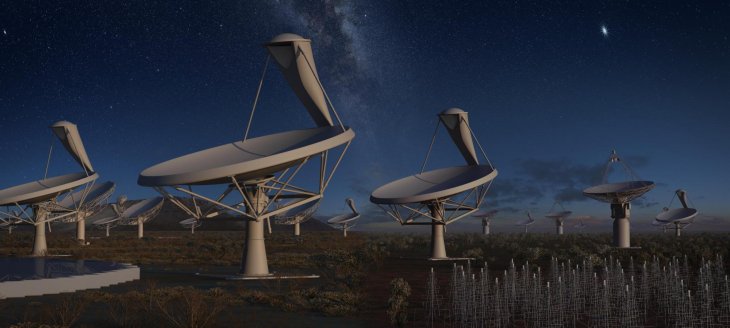

The CHIME, an interferometric radio telescope at the Dominion Radio Astrophysical Observatory in British Columbia, Canada, is hoped to detect at least 1 FRB per day when it comes into use this year. Things were promising last year in its test when it found dozen of these bursts, leading scientists to think that they would be able to conduct more tests on FRBs this year.

A magnetar might be the source we have been looking for

The joint achievement of Metzger, Ben Margalit, and Lorenzo Sironi was made with the contribution of the biggest breakthrough in FRBs, which is the study of Laura Spitler and her team on the first cosmic burst to repeat, a one-of-a-kind event. Since the FRBs do not usually repeat, scientists have faced with a ton of trouble locating their source, which leads them to believe that they may come from a place out of our galaxy.

At first, they thought that these bursts sourced from a dwarf galaxy. After taking all the evidence they can find into consideration, they found out that the source might be an extreme cosmic area surrounded by powerful magnetic fields. Another finding revealed that the bursts have a vague radio glow around them. Last year, Spitler team announced that each burst actually has some sub-burst having lower radio frequencies.

This sub-burst finding shares a striking resemblance to a theory related to nuclear weapons in the 1950s. As the explosion increases in size, it picks up gas along with it, which helps decrease the speed of the shock. As a result, radiation sourced from the shock changes its frequencies to lower levels.

This incident might be the answer for why FRBs happens, Metzger said.

Fast forward to today, the team has made their work public, which stands on the explanations of the only burst that repeated. In detail, the making of fast radio bursts goes like this. A young magnetar releases positrons, electrons, and even iron. These particles crash into the ones from previous blasts and create a shock with magnetic fields getting stronger.

The electrons then travel along the magnetic fields’ lines, which generates radio wave bursts. As the shock decreases in speed, the waves change to a lower frequency.

From what Metzger and his team found out, we now have a theory on the attributes of FRBs, including the lower in frequencies, the release of X-ray or gamma-ray, and the gap between a flare and a burst. Of course, let not forget the magnetars. The galaxy in which the bursts happen should contain a lot of these young neutron stars.

The theory makes sense in a lot of ways, but it cannot rule out others that also make sense. Another study suggests that FRBs might be the result of two neutron stars merging. When they hit something like a white dwarf or a black hole, this incident could also make fast radio bursts. Other possible theories include when a neutron star’s magnetic fields’ lines pulled out by plasma winds.

We are not whether FRBs are the result of only one event or not. While Metzger’s theory stands on a quite solid foundation of the repeating burst, some other scientists remain skeptical as it seems to be built to fit that only incident. It is possible that other bursts do not repeat like what Metzger based his study on because they have different sources. And if astronomers wait for a little longer, these bursts might repeat.

However, with the CHIME ready to be put to work, scientists expect that their first testing round will occur in April. Participating in this race to find and confirm the exact source of FBRs are the Australian Square Kilometer Array, a large multi-radio telescope project and in the next few years, HIRAX, located in South Africa, Rwanda, and Botswana.

Australian Square Kilometer Array will soon join the race for the answer

After years of working and forming theories, in February, in a gathering in Amsterdam, astronomers interested in fast radio bursts finally came up with something prominent, which is the neutron stars might be the source of the bursts and Metzger’s theory, which pinpointed the cause to the exact stars, is perfect timing, said Amanda Weltman, a South African theoretical physicist at the University of Cape Town.

Researchers are still working and debating the model which Margalit, Metzger’s teammate brought to the meeting and they have not yet be convinced entirely. No conclusions have yet to be announced but they said that they were close to convergence.

Featured Stories

Features - Jan 29, 2026

Permanently Deleting Your Instagram Account: A Complete Step-by-Step Tutorial

Features - Jul 01, 2025

What Are The Fastest Passenger Vehicles Ever Created?

Features - Jun 25, 2025

Japan Hydrogen Breakthrough: Scientists Crack the Clean Energy Code with...

ICT News - Jun 25, 2025

AI Intimidation Tactics: CEOs Turn Flawed Technology Into Employee Fear Machine

Review - Jun 25, 2025

Windows 11 Problems: Is Microsoft's "Best" OS Actually Getting Worse?

Features - Jun 22, 2025

Telegram Founder Pavel Durov Plans to Split $14 Billion Fortune Among 106 Children

ICT News - Jun 22, 2025

Neuralink Telepathy Chip Enables Quadriplegic Rob Greiner to Control Games with...

Features - Jun 21, 2025

This Over $100 Bottle Has Nothing But Fresh Air Inside

Features - Jun 18, 2025

Best Mobile VPN Apps for Gaming 2025: Complete Guide

Features - Jun 18, 2025

A Math Formula Tells Us How Long Everything Will Live

Read more

ICT News- Feb 19, 2026

Escalating Costs for NVIDIA RTX 50 Series GPUs: RTX 5090 Tops $5,000, RTX 5060 Ti Closes in on RTX 5070 Pricing

As the RTX 50 series continues to push boundaries in gaming and AI, these price trends raise questions about accessibility for average gamers.

ICT News- Feb 20, 2026

Tech Leaders Question AI Agents' Value: Human Labor Remains More Affordable

In a recent episode of the All-In podcast, prominent tech investors and entrepreneurs expressed skepticism about the immediate practicality of deploying AI agents in business operations.

ICT News- Feb 18, 2026

Google's Project Toscana: Elevating Pixel Face Unlock to Rival Apple's Face ID

As the smartphone landscape evolves, Google's push toward superior face unlock technology underscores its ambition to close the gap with Apple in user security and convenience.

Comments

Sort by Newest | Popular